The Tumultuous 15th Century

The 15th century provides us with many of our stock, childhood images of the "Middle Ages": the knight in shining armour, the joust, even elegant ladies in tall, pointed hats! Yet it is a paradox, for by this time, many of the hallmarks of medieval society had already faded and were being replaced by a culture associated with the Renaissance. Feudalism, that uniquely "medieval" political system, had effectively been dead for centuries. Medieval monarchs increasingly looked to develop effective, professional armies that could be more adaptive, better trained and able to stay longer in the field. At the same time that his employers were reexamining his role on the battlefield, the knight's newly completed harness was increasingly challenged by a combination of arms, in the form of pike, bow and gun, and they would soon unseat him from his place at the center of military society. Even the joust had become an increasingly artificial, international sport, rather than serious military training. Meanwhile, intrepid merchants became the new knighthood of Europe, seeking new wealth in Asia and Africa, and launching what has been called the "Age of Discovery".

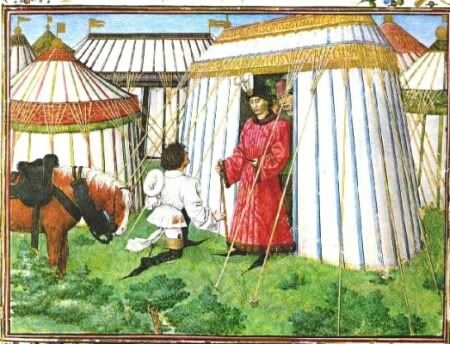

The 15th century was a period of drama and elegance, as well as an idealized romanticizing of chivalric ideals. An illustration from Rene d'Anjou's "Book of Love". (1465)

In the year 1400, England and France were still locked in the Hundred Years War, and France was ruled by a mad king, with its worst defeats still yet to come. Emboldened by the weakening of the French monarchy, the powerful Dukes of Burgundy continued to grow more autonomous, building in all but name an independent kingdom, and a court that became the cultural center of northern Europe. In Iberia, the ancient Muslim culture of Al Andalus had been driven back by the Spanish kingdoms, until only the small kingdom of Granada remained, giving the Iberian Christians more time to war against themselves. Meanwhile, far to the east, the battle of Cross and Crescent was taking a very different course: the ancient Byzantine Empire was making its last stand against the inexorable advance of the Ottoman Turks. And through it all, the bankers and trading houses of Italy and the Hanseatic League grew ever wealthier.

By 1500, the "Middle Ages" as we think of them had been all but swept away. France had emerged victorious from the Hundred Years War and brought her rebellious duchies to heel, including Burgundy, making the monarchy stronger than it ever had before. England, on the other hand, and proceeded from the disastrous loss of her French territories into a bloody, thirty year long civil war, the War of the Roses, that saw the Plantagenets lose the crown of England after nearly three and a half centuries of unbroken rule. In 1453, Constantinople at last fell to the Turks, bringing to an end the last true survivor of the ancient Roman Empire. Meanwhile, the Spanish kingdoms of Castille and Aragon had driven out the last of the Muslim rulers, and had united into a single Spanish kingdom, creating what was soon to become a European superpower.

But during the intervening years of this century, European society would undergo far more change than just political upheaval. A new intellectual culture was brewing that would bring sweeping changes in art, science, fashion and a drive for exploration. The Renaissance was being born.

Humanism

It is often argued that the sweeping changes of the 1400s were driven first and foremost by a change in intellectual culture that returned to a reading of classical authors, put a new emphasis on secular topics and legitimized the striving for personal accomplishment. This new ideology was Humanism.

The Middle Ages had been dominated by the intellectual culture of Scholasticism, which focused on resolving contradictions between famous Classical authors. Over time, the commentaries by these later scholars would develop an authority almost equivalent to that of the original author, so that a trained scholar might say that he had studied Aristotle without ever having read an actual word written by Aristotle himself! In the late 14th century, however, a new intellectual movement began to take shape in northern Italy. Because of their mercantile dominance, the Italian cities had long since had a need for highly educated, literate men with secular backgrounds. Initially, such a clerk, notary or lawyer was known as a humanist if he was a student or teacher of Latin and Latin literature but was not a Churchman. These "humanist" scholars began to rediscover many Latin and Greek texts, particularly poetic, historical and rhetorical works that had been neglected or even oppressed by clerics. By the mid-fifteenth century, the philosophy of Humanism had come to describe the studia humanitatis - a complete curriculum of grammar, rhetoric, moral philosophy, poetry and history as learned from a direct study of Classical authors. Above all, these Humanists asserted that, as Man was created in the image of God, his unique ability to reason, appreciate beauty and to create and fashion objects was an inherently divine quality. As such, art and science were twin pillars that not only ennobled, but essentially sanctified man.

In the century that followed, Humanist political writers such as such as Niccolo Machiavelli and Thomas More would use the idea of Classical authors to criticize their governments, while new exposure to Plato would lead theologians such as Giordano Bruno and Martin Luther to challenge Church leaders not only politically and morally, but at the very philosophical underpinnings of their Aristotelian world view.

Art and Science

The Humanist worldview naturally intermingled Art and Science. Noted artists such as Leonardo da Vinci made observational drawings of anatomy and nature, while disciplines such as music and fencing were considered to be both a science and an art, as they were governed by certain undeniable physical laws of proportion and time, but were applied in a creative, ever-changing fashion. The most noted artistic change of the 15th century was the development towards a "realistic" sense of perspective. Masters such as Giotto di Bondone (1267-1337) had begun this process in the 14th century, but it did not achieve its full-flowering as a formal "technique" to be studied and used as a measurement of the artist's skill, until it became popularized by the architect-sculptors Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) and Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472). Once a quest for realism had begun in one artistic element, artists quickly began to apply it to others, such as light and shadow. Inspired by the Humanist fascination with beauty and nature, they sought to more carefully render natural elements, most specifically, the human form, and this was expressed in the peerless works of da Vinci and Raphael that appeared in the last decades of the century

Jan van Eyk's famous "The Arnolfini Portrait" (1434)

But the Italians had not cornered the market on artistic innovation, and under the patronage of the wealthy Burgundian Dukes, a new "natural" school developed in the Netherlands, building around the work of Jan van Eyck (1385 -1441), who is also credited with the introduction of oil paint and canvas.

The fusion of art and science was perhaps most felt in the world of architecture, which became influences by a rediscovery of the writings of the 1st century mathematician Vitruvius. The architectural revolution of the 15th century began when Filippo Brunelleschi built the dome of the Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence (1419-1436). Based upon the famed Pantheon in Rome, it would be the first free-standing dome of any significant size built in Western Europe since the fall of the Roman Empire.

Brunelleschi's dome atop the Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore (1419 - 36)

Throughout the century a vast array of other innovations and inventions, such as the printing press (1455), the woodcut (1400 - 1450), the harpsichord (c.1460), canal locks (1481), the distillation of malt into whiskey (c.1460). Yet the most significant development of the era was probably not any one discovery, but rather a process for discovery, based on empirical evidence. This method was the "scientific method" that has driven western science ever since.

Fashion

The fashion trends of the 1400s followed the same trend towards exuberant extremes reflected in the rest of society during this period. As the worst of the Black Death (1348 - 1350) lay long in the past, the changes in European society it had created included a tend towards greatly empowered, urban "middle classes". These tradesmen, guildsmen and merchant-princes were nowhere as powerful or influential as the Italian city-states, or the Flemish cities under the rule of the Dukes of Burgundy.

Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy and his court, in a miniature by Rogier van der Weyden (1477).

With England and France mired in the Hundred Years War and its aftermath and then the English Wars of the Roses through most of the century, the glittering, the fashion-conscious, and sharp-witted Duke Philip the Good (ruled 1419-1469) had turned Burgundy into an autonomous kingdom in all but name, and had used his control of the trading cities Holland and Flanders to the acquire the finest English wool, eastern silks and Italian fashions.

Meanwhile, in Italy the old nobility had long fallen to mercantile republics or military despots. In many cases, the latter simply assumed the old hereditary titles of marchese, count or duke, whether they came from old noble families or were upstarts raising themselves up as the new nobility. Desiring to establish their legitimacy, these despots sought to make their courts the envy of Europe. Those who embraced the new ideals of Humanism became great patrons of art, science and learning. The lord acquired renown as a man of culture, learning and wealth, gaining additional civil or military service from the courtier, while the courtier gained far more: stable financial support, prestige, and a chance to develop his work without having to fight against the pressure of daily life.

The elegant houppelande, first appearing in the late 14th century, would dominate the fashions of the nobility throughout the first half of the 15th century.

The end result was that, there was a class of wealthy commoners in the midst of these extravagant courts who had the wealth and connections to successfully mimic, and sometimes exceed, the fashions of the nobility, regardless of any sumptuary laws. This thereby prompted the nobility towards ever more elaborate and extravagant fashions themselves. It also led to the first real trend towards clear "national" variances in European fashions.

At end of the previous century, the voluminous houppelande had become a popular fashion for both men and women. The houppelande continued to be popular in Burgundian, French and English circles until well into the 1470s. Although it could be worn anywhere from floor to knee length, in all cases it became progressively more pleated, fitted with a high collar and tall, stuffed shoulders. At the same time, a counter-fashion was evolving in Italy and the south, as the old men's cotehardie became shorter and tighter, until it evolved into the revealing doublets and hose associated with the Italian Renaissance. Both houppelande and doublet would become popular throughout Europe, but with unique regional styles, such as the Italian fashion of wearing the doublet with a short, pleated tabard called the giornea, or the Burgundian fashion of the mid-century for the wealthiest of men to dress in solid black.

Feminine fashion went through its own evolution as well. The old cotehardie and sideless surcoat persisted through the early decades of the century, with the cutouts of the surcoat becoming progressively wider. However, it was again the late 14th century houppelande, fitted with a high collar and wide sleeves that was to influence feminine fashion throughout most of the century. By 1450, the northern Europe fashion had developed a low V-neck that revealed glimpses of the undergown below. The full, long sleeves continued to be worn, although they were increasingly more fitted with wide, turned-back cuffs. Meanwhile, in Italy, the low V-neck and scoop-neck of the early decades gave way to a neckline that was worn high in front with a lower V-neck at the back, often worn with a sleeveless tabard, or giornea. This evolution would lead towards a series of new fashions in the final decades of the century, including the first appearance of puffed and slashed sleeves that would last for two centuries.

Meanwhile, accessories assumed a new level of importance, particularly headwear. The old 14th century rolled chaperone evolved from a rolled-up hood into a unique, padded hat, hoods and turbans assumed new forms, and men's hats took on a variety of shapes, including some oddly familiar to modern eyes (one example looking much like the offspring of a derby and a ten-gallon hat!). But for the lady of means, the height of distinction was in multitude of headdresses that came in and out of fashion during the 1400s, many of which can only be best described as a Gothic arch on your head!

Throughout the High Middle Ages, Europeans had been looking for more effective trade routes into Asia. Ironically, the same Mongol invasions that had destabilized much of Eastern Europe in the 13th century also united great swathes of Asia under a single rule, allowing Europeans merchants, mostly Italians, to more easily travel into the Far East. The most famous voyager was of course Marco Polo, who traveled throughout the Asia from 1271 to 1295, and became a guest at the court of Kublai Khan. His journey recorded a Travels was read throughout Europe. Yet Polo's voyage had little immediate effect, for the collapse of the Mongol Empire, the devastation of the Black Death and the rise of the aggressive Ottoman Empire effectively destroyed any chance at Europeans increasing overland exploration or trade.

But Marco Polo was not forgotten, and entered a new period of fame in the 15th century Niccolo da Conti published an account of his travels to India and Southeast Asia in 1439. There was again an interest in new trade routes East, and this interest came none too soon, for with the fall of Constantinope in 1453, the old routes were now firmly under Ottoman control, and barred to Europeans. Fortunately, at the same time that a way around the Muslim lands of Asia Minor and North Africa were becoming viewed as crucial to European businessmen, the people of the Iberian peninsula had already begun developing the key to unlock the road East. This was the invention of new ships, the carrack and the caravel, "round ships" developed and influenced by North African models and better suited to open ocean voyage. At the same time, Humanist authors continued to rediscover classical accounts of geography and exploration, and became convinced that there was a way around Africa.

The 15th century saw the first swell of expeditions that would launch the "Age of Exploration", and it was the Portuguese who led the way. The first of these voyages was launched by the Prince Henry the Navigator (1394 - 1460). Sailing out into the open Atlantic, Henry discovered first the Madeira Islands in 1419 and the Azores in 1427, and quickly established colonies on both. From here he turned to West Africa, seeking a way to bypass the trans-Saharan trade routes in the hope of finding gold, slaves and the fabled Christian kingdom of Prester John. By the 1440s the Portuguese had pushed south of the desert and into the interior, and although they did not find Prester John, they found a vigorous trade in gold and slaves. But the crucial breakthrough came in 1487, when Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope and proved that access to the Indian Ocean was possible. Eleven years later, Vasco da Gama (1460 - 1524) successfully reached India.

The Spanish kingdoms had been slower to respond and now anxiously needed their own check on Portuguese domination of the African entire. With the union of Castille and Aragon, the newly united Spain suddenly had the resources to launch an expedition of its own, with the hope that a Genoese sailor was right that the African route to India could be by-passed entirely by sailing straight west across the Pacific Ocean. When Christopher Columbus (1451 - 1506) returned with claims of having reached "the Indies" it was unclear precisely where he had been and what he had found, but it was clear that he had been somewhere.

At the dawn of the 16th century, while the old maritime powers of Genoa and Venice continued to war with the Ottomans for control of the eastern Mediterranean, the Italian city-states braced themselves for foreign invasion, and the glory of the Burgundian court became the memory of the previous generation, a New World loomed and the balance of European power began to shift to the children of Iberia.

1 comment:

good site!

Post a Comment